Zero Chippenham member James Bradbury talks about his experience of installing and living with an Air Soured heat pump. James’ house is a 1980s standard Chippenham estate house with two minor extensions. It has cavity wall insulation.

Introduction

I’ve been seeing a lot of interest online about heat pumps and some confusion about what they are and how they work. We had one installed in our home a couple of months ago. We’re pleased with it and I’ll describe our experiences below, but first I’ll give a quick intro to heat pumps.

What is a heat pump?

A heat pump is an electrically powered device for moving heat from one place to another. This is in contrast to direct heating which turns electricity into heat. In the domestic setting this means getting heat from some outside source and moving it into the building for heating or hot water. Crucially the pump’s output temperatures can be significantly higher than the input.

If that seems like magic, think about what a refrigerator does. A heat pump does the same in reverse – moving heat from one place to another.

Because of this, heat pumps are much more efficient than direct heating. In good conditions a modern air source heat pump can provide 3 to 4kW of heat for each kW of electricity consumed.

What kinds of heat pumps are there?

Heat pumps come in at least three flavours, depending on the source of heat they use.

Air-source heat pumps (ASHP) are most popular as they can be installed in most places. They typically have a large fan to pass ambient air over the heat sink. They will work at air temperatures as low as -20 degrees C and are popular in Scandanavia, but become less efficient as the outside temperature drops.

Gound-source heat pumps take heat from underground, sometimes a pair of deep boreholes, or shallow pipes over a large area. The ground stores a large amount of heat accumulated over many months. GSHPs have the advantage that they are not affected by air temperature so can achieve better average efficiencies. The downside is that they need more space to install and the work is messy and expensive.

Water-source heat pumps take heat from a natural water source such as a river. I don’t know much about them as they are less common. I would imagine they are cheaper than ground source heat pumps and more efficient than air-source due to the flow of water. I suppose the risk might be that the water source either freezes or dries up.

In the UK most heat pumps provide heat to common water-filled radiators and hot water system, making them compatible with most legacy central heating systems. I understand that in countries with hotter climates they often provide warm and cold air to heat and cool the room with the same equipment.

For more in-depth information on heat pumps, see this guide from the Energy Saving Trust.

Our experience of an air-source heat pump

Our heat pump was installed in early February 2023. We made use of the UK’s Boiler Upgrade Scheme to get £5000 towards the cost of our heat pump. In addition we paid around another £10000 including all parts and labor. We had a Mitsubishi Ecodan on the recommendation of a local company who had themselves been recommended by a friend. In retrospect, while their equipment is said to be reliable, Mitsubishi have rather dubious ethical credentials and if choosing again we might go for a Vaillant, Kensa or MasterTherm.

Installation

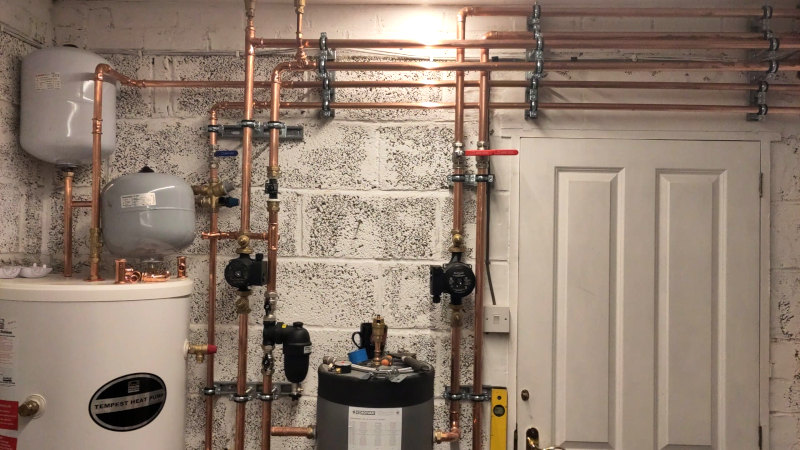

Our install was slightly complicated as we have some 8mm mircobore piping in our house. This means we needed an extra buffer tank so that the central heating water can be pumped around faster than the heat pump water. That added an extra £800 to the bill and took a little more space in our garage.

Copper pipes and water cyclinders attached to the wall inside a garage.

Speaking of space, we used a fair bit of space in the garage for the hot water cylinder, aforementioned buffer tank and a lot of pipework. This had to be linked to the condenser outside, which meant two wide copper pipes and a few wires through a few walls and across our kitchen wall. We discussed where this should go with the installers and they came up with a good solution keeping the distance as short as possible. This keeps costs and heat loss down. All the pipes were insulated by the installers, although I added a bit extra to the fiddly bits myself.

In addition to the heat pump and piping, we took the installers’ advice and upgraded three radiators. Two of these needed upgrading anyway as they were rather rusty.

Performance & Economy

Our old combi gas boiler was already set up to run as efficiently as possible by reducing the flow temperature. It was only about five years old, so should be fairly efficient. I sold it to a friend who should be able to reduce their gas use and costs as a result.

The installer provided calculations that showed we would save about £10 per year. Clearly not a huge financial incentive, but that was never our main motivation. It also didn’t take into account what we might pay for our electricity in the future. In particular, the fact that we had solar panels would greatly reduce the cost of daytime use.

I put together a spreadsheet with our domestic energy usage for Jan-Mar 2022 and 2023 so I could make some comparisons. The trouble is that it’s very difficult to compare like with like due to many confounding factors. To name a few: energy prices, outside air temperatures, usage patterns. For example, I don’t have any record of how many times we used the oven during these months, which consumes significant electrical energy. However, I do have a few qualitative observations I can make with confidence.

Cost of running in February 2023 was slightly higher than January 2023

Why should this be? Aren’t heat pumps meant to be very efficient?

The cost difference is mostly because electricity from the grid cost us ~44p/kWh in the day and ~16p/kWh at night while gas costs ~10p/kWh. As we have solar panels, this will change with longer days and more sunlight. February is a poor month for solar.

Finally, as the temperatures dropped to around freezing a few times, the heat pump would have been less efficient. At times it iced up and would occasionally perform a defrost cycle which presumably adds to the running cost. When the outside temperature is over 5 degrees C (41F), the coeffcient of performance (COP) increases.

The data from the heat pump control panel suggests that February’s COP was 2.21 and March was 2.75.

Energy and carbon emissions

Our overall energy use with the heat pump appears to be about half as much as with the gas central heating. It is likely that our carbon emissions are reduced by at least this much, depending partly on the current carbon intensity of the grid when we’re using it. This is further improved when we have strong daylight or sunshine as we can make use of our solar panels. We only get paid 4.1p/kWh for solar export, so that could be considered the cost of using our solar energy, which is much cheaper than importing from the grid.

We have additionally bought shares in a Ripple wind farm, although it is not finished yet. When complete this will further reduce the cost of our electricity and effective carbon footprint.

Thermal comfort

Our thermal comfort with the heat pump was noticeably better than the previous month on gas. With gas, we tended to heat our home only during the evenings and briefly in the morning. Heating the entire house all day, even while working from home in a single room, seemed like an extravagance. At times the room temperature dropped to 15 degrees C (59F).

Heat pumps are intended to be run most of the time as, due to the lower flow temperatures (35-50 degrees C rather than 60-80), it takes longer to warm up. So that’s what we do and now our home is at a constant temperature of 19 degrees C (66F) during the day, dropping to 18 at night.

It feels strange at first, that the radiators are sometimes not very warm to the touch and never hot enough to hurt your hand. Yet the house is consistently comfortable.

I think when using gas to heat the home rapidly and infrequently, as we did before, it’s mostly the air which gets heated. In contrast the heat pump is on a gentle heat all the time. This means that every object in the house is slightly warmer, as are the internal wall surfaces. So it takes longer to cool down and when we open a window for fresh air the heat doesn’t seem to disappear immediately.

Domestic hot water

We have a 200L tank in the garage for hot water as seen above. This seems to be sufficient for our showers, washing up, etc. The good thing about having it in a well-insulated tank is that we can choose when it gets heated. I’ve set this to happen during the night, when electricity is cheap and late morning, when we often have excess solar power. For those with solar power but no heat pump, it can make sense to use excess solar to heat water with an electric immersion heater. Our system included two of these for emergency use and a regular anti-legionella cycle. However, using the heat pump to heat the water to 50 degrees C might use only a third or a quarter of the electricity. I’m told the tank will lose 1 degree of heat after 17 hours. In the summer, most of our hot water could be free.

What’s worth noting is that the heat pump won’t heat water and provide heating at the same time. That has never been an issue as it seems to take less than an hour to heat the water and the house doesn’t cool down much in that time.

Getting off gas

We still have a gas supply to our house for a four-ring hob, but we intend to change this for an induction hob in the near future. Until then we’re paying around £9 a month in standard charges. This should be cheaper and, more importantly, healthier.

Noise

A major concern for those considering an air source heat pump is the noise of the condenser unit that sits outside. We’ve not found that a problem at all. If I stand next to it when the fan is running, I can certainly hear it, but more than a couple of metres away, I can only hear it on a very still day. In the summer, when we’re likely to be sitting out in the garden, the fan won’t usually be running at all.

What is sometimes noisy is the internal pump for the radiators. This runs at a higher rate than most due to our microbore piping. However, I turned it down to the lowest of three settings so the noise is rarely enough to be annoying. This does not seem to have affected the heating.

Other features

The Ecodan comes with an easy to use programmable panel to control timings and temperatures as well as a simple remote unit which acts as a thermostat – so it therefore needs to be placed carefully. There is also a smartphone app which will provide current and historical temperature data as well as allowing you to temporarily change the target temperature or turn the hot water on. However, it doesn’t allow you to edit the settings on the main control panel.

Conclusion

Overall we’re pleased with the heat pump and service from installers Summit Energies. I understand that there is a regulation that specifies the system must be able to reach 21 degrees C even when the temperature outside is -10 degrees C. We never have the thermostat as high as 21, so I guess they slightly overspecified the system. They can’t easily tell how much microbore is hidden in the walls and how much is wider piping. So they err on the side of safety. I think the central heating pump could probably have been a less powerful one.

But the main improvement is thermal comfort. Our house is always the temperature we want and, for most of the year, it will cost us less to run. Our carbon emissions from heating have been significantly reduced and, as the grid continues to decarbonise, will reduce further.

In addition to his contributions to Zero Chippenham, James is a keen cyclist and a member of the Chippenham Cycle network.

A passionate environmentalist, James is an elected Independent town councillor for Cepen Park & Derriads, Chippenham. You can find out more about James on his blog James Thinks.